Adapted from a political memoir

The Manchanda Connection

by Diane Langford

‘As Richard Wright found long ago in America, black and white

descriptions of society are no longer compatible’

Salman Rushdie

The Campaign Against Racial Discrimination operated from a grimy cubbyhole in a tenement off Brick Lane, behind the Toynbee Hall. I volunteered there most evenings throughout 1966-67. By day, I was a temp, courtesy of Kelly Girl. If you were white, it was easy to get jobs back then. If you didn’t like the work, you could walk out at lunchtime and the agency would send you elsewhere in the afternoon. Whenever I could afford to, I’d take a sickie and work all day at the CARD office.

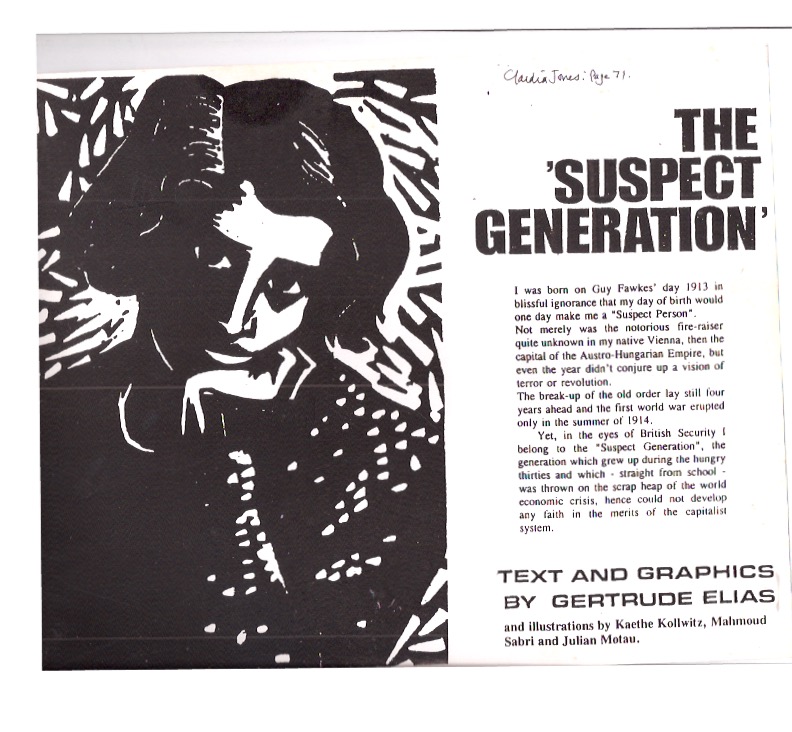

Julia Gaitskell and Antony Lester were two establishment figures that displayed an attitude of ownership over CARD, while Dr David Pitt and Jocelyn Barrow were among the campaign’s eminent Black co-founders. Claudia Jones was briefly involved, shortly before her untimely death.

The office was managed by Jamaican activist, Ralph Bennett, whose wages were paid directly out of the pocket of Dr Pitt. I typed fund-raising letters, was intermittent filing clerk and discreet eavesdropper when Gaitskell and Lester dropped by and talked revealingly amongst themselves about their respective political ambitions. Johnny James of the Caribbean Workers Association was a frequent visitor, though never at the same time as Lester and Gaitskell, who only turned up occasionally to check up on things.

It was from James, who always wore a Mao button on his lapel, that I first heard the name ‘Manchanda.’

‘They’re saying Manchanda sold Claudia Jones’ ashes to the Chinese,’ he reported. Who was Manchanda and why would he sell Claudia Jones’ ashes to ‘the Chinese?’ Nobody knew the answer.

During my time at CARD, Gaitskell and Lester were swept from power by an overwhelming vote at an AGM, described by them as a ‘coup.’ The pair immediately called a press conference blaming ‘Maoists’ and ‘Black Power’ advocates for the unexpected and apparently unacceptably high number of Black and Asian people who’d turned up at the Conway Hall to vote them out. Bennett and I had been knocking on doors in Brixton, Hackney and Southall to mobilise people to come along. Coach loads did. Amazement and horror was reflected on the faces of the old white guard when they arrived to find the hall packed with delegates from the Black and Asian communities.

The Sunday Times Insight Team produced a scurrilous, sensationalised account of the event in their book Black Man in Search of Power accusing Dr Pitt of ‘opening the palace gates from within.’ Years later, David became one of the first Black Lords, preceded only by the cricketer, Learie Constantine. He took the name Lord Pitt of Hampstead, not for Hampstead, London NW3, though that was where he then lived, but Hampstead in Trinidad.

By 1967, anti-Vietnam war protests were hotting up. I joined Australians and New Zealanders Against the War that met every Friday night at the Marquis of Granby in Cambridge Circus. I remember a dry as dust presentation by Eric Hobsbawm and later being handed a much more interesting Britain-Vietnam Solidarity Front leaflet by a bearded Aussie.

The first time I saw Manu was at the front of an anti-Vietnam war demonstration, going along Park Lane. A line of policemen with riot shields blocked the road. A senior officer wearing a peaked cap, his uniform covered with silver badges, stepped out and held up his hand like a traffic cop. We straggled to a halt. A middle-aged man went forward from our side to meet him. I was near enough to hear the conversation. Manu was much shorter than the policeman but his presence was far more powerful. His face was calm; panda eyes behind tinted NHS spectacles. He wore an astrakhan hat and a grey overcoat. From his pocket he produced a rumpled map. His movements were graceful, the absence of machismo striking. As I observed this tableau, I was exhilarated by his complete lack of awe.

‘This is the route we agreed,’ he said, without raising his voice. ‘We’re going forward.’

He lightly prodded the inspector’s chest with a forefinger, causing the policeman to step back with a surprised expression. The crowd surged forward and the line of police melted away.

Later, I heard Manu’s voice on the radio. Cartoons had appeared in the red-tops depicting the two ‘resident aliens,’ Tariq Ali and Manchanda, locked in a dispute about where the next national demonstration should take place.

A prim BBC announcer asked, ‘So, Mr Manchanda, can you explain the controversy over the route of the march on Sunday?’

‘Tariq Ali is a revisionist playboy who’s planning to take people on a guided tour of the West End and into Hyde Park. The lair of U.S. imperialism is the American Embassy in Grosvenor Square and that’s where the protest should be made.’

I liked Manchanda’s melodious, ironic tone.

When I saw him next, in a packed meeting at a flat in Golders Green, I noticed his clean-shaven, smooth skin, dark eyes, dainty hands and feet. He held his head slightly to one side as he listened, with a far away, slightly depressed air.

Life on earth, I’d previously believed, consisted of millions of tiny coincidences. Now I began to understand that there was a system at work. Nothing happens spontaneously and spontaneous action cannot change the system under which human society is structured. We have to organise for change!

Julia Gaitskell and Antony Lester were two establishment figures that displayed an attitude of ownership over CARD, while Dr David Pitt and Jocelyn Barrow were among the campaign’s eminent Black co-founders. Claudia Jones was briefly involved, shortly before her untimely death.

The office was managed by Jamaican activist, Ralph Bennett, whose wages were paid directly out of the pocket of Dr Pitt. I typed fund-raising letters, was intermittent filing clerk and discreet eavesdropper when Gaitskell and Lester dropped by and talked revealingly amongst themselves about their respective political ambitions. Johnny James of the Caribbean Workers Association was a frequent visitor, though never at the same time as Lester and Gaitskell, who only turned up occasionally to check up on things.

It was from James, who always wore a Mao button on his lapel, that I first heard the name ‘Manchanda.’

‘They’re saying Manchanda sold Claudia Jones’ ashes to the Chinese,’ he reported. Who was Manchanda and why would he sell Claudia Jones’ ashes to ‘the Chinese?’ Nobody knew the answer.

During my time at CARD, Gaitskell and Lester were swept from power by an overwhelming vote at an AGM, described by them as a ‘coup.’ The pair immediately called a press conference blaming ‘Maoists’ and ‘Black Power’ advocates for the unexpected and apparently unacceptably high number of Black and Asian people who’d turned up at the Conway Hall to vote them out. Bennett and I had been knocking on doors in Brixton, Hackney and Southall to mobilise people to come along. Coach loads did. Amazement and horror was reflected on the faces of the old white guard when they arrived to find the hall packed with delegates from the Black and Asian communities.

The Sunday Times Insight Team produced a scurrilous, sensationalised account of the event in their book Black Man in Search of Power accusing Dr Pitt of ‘opening the palace gates from within.’ Years later, David became one of the first Black Lords, preceded only by the cricketer, Learie Constantine. He took the name Lord Pitt of Hampstead, not for Hampstead, London NW3, though that was where he then lived, but Hampstead in Trinidad.

By 1967, anti-Vietnam war protests were hotting up. I joined Australians and New Zealanders Against the War that met every Friday night at the Marquis of Granby in Cambridge Circus. I remember a dry as dust presentation by Eric Hobsbawm and later being handed a much more interesting Britain-Vietnam Solidarity Front leaflet by a bearded Aussie.

The first time I saw Manu was at the front of an anti-Vietnam war demonstration, going along Park Lane. A line of policemen with riot shields blocked the road. A senior officer wearing a peaked cap, his uniform covered with silver badges, stepped out and held up his hand like a traffic cop. We straggled to a halt. A middle-aged man went forward from our side to meet him. I was near enough to hear the conversation. Manu was much shorter than the policeman but his presence was far more powerful. His face was calm; panda eyes behind tinted NHS spectacles. He wore an astrakhan hat and a grey overcoat. From his pocket he produced a rumpled map. His movements were graceful, the absence of machismo striking. As I observed this tableau, I was exhilarated by his complete lack of awe.

‘This is the route we agreed,’ he said, without raising his voice. ‘We’re going forward.’

He lightly prodded the inspector’s chest with a forefinger, causing the policeman to step back with a surprised expression. The crowd surged forward and the line of police melted away.

Later, I heard Manu’s voice on the radio. Cartoons had appeared in the red-tops depicting the two ‘resident aliens,’ Tariq Ali and Manchanda, locked in a dispute about where the next national demonstration should take place.

A prim BBC announcer asked, ‘So, Mr Manchanda, can you explain the controversy over the route of the march on Sunday?’

‘Tariq Ali is a revisionist playboy who’s planning to take people on a guided tour of the West End and into Hyde Park. The lair of U.S. imperialism is the American Embassy in Grosvenor Square and that’s where the protest should be made.’

I liked Manchanda’s melodious, ironic tone.

When I saw him next, in a packed meeting at a flat in Golders Green, I noticed his clean-shaven, smooth skin, dark eyes, dainty hands and feet. He held his head slightly to one side as he listened, with a far away, slightly depressed air.

Life on earth, I’d previously believed, consisted of millions of tiny coincidences. Now I began to understand that there was a system at work. Nothing happens spontaneously and spontaneous action cannot change the system under which human society is structured. We have to organise for change!

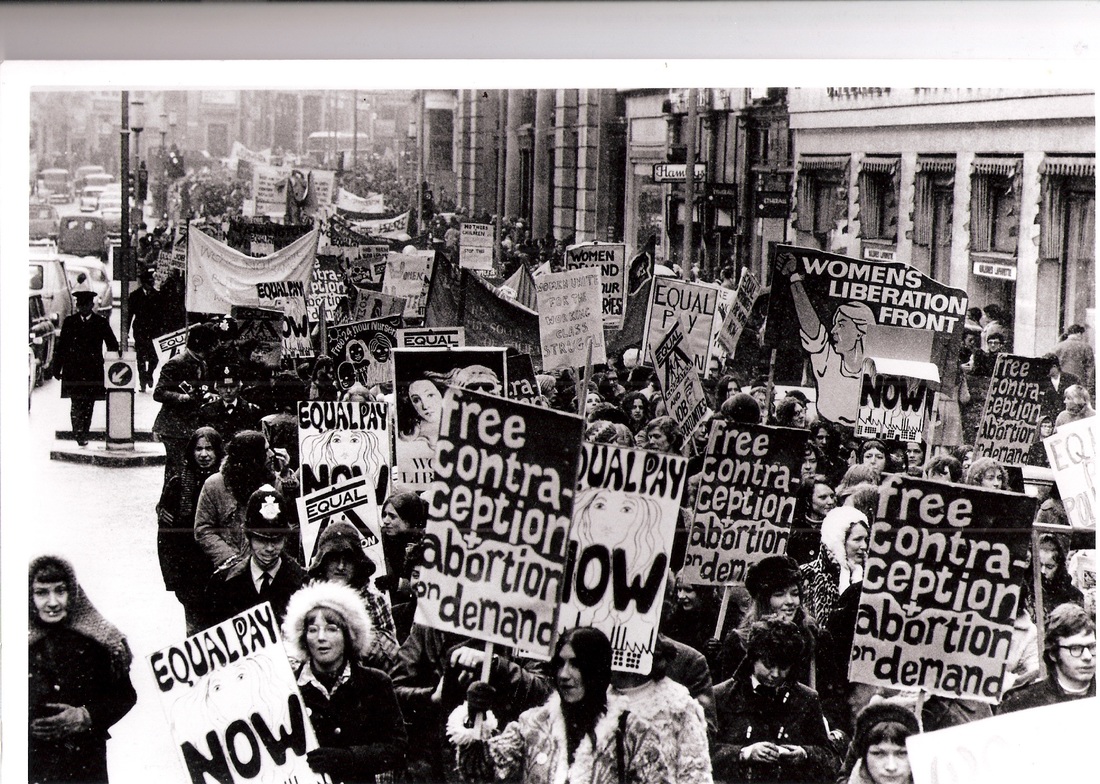

On Sunday, October 27, 1968, I waited at the corner of Northumberland Avenue with Mary Tyler, a teacher and fellow-volunteer I’d met at the CARD office. We were given a bit of pasteboard with the name of a solicitor printed on it in case of arrest, and an invitation to go to the Union Tavern, a pub near Kings Cross, afterwards, to check who was missing and possibly in need of rescue from a police cell.

We heard the marchers approaching, shouting, banging drums, blowing whistles. Police on horses rushed past. As the demonstration reached the corner at Trafalgar Square, a group of running men and women with loud hailers worked the crowd, ‘Don’t be diverted. Follow the red banner to the US Embassy!’

Mary and I inserted ourselves into the swathe of bodies that peeled off in the direction of Grosvenor Square. Tall men on either side of me linked arms and I felt myself being lifted off the ground. All I could think about was staying alive in the crush. When we reached the US Embassy the police were waiting, riot shields poised. Horses were snorting and steaming and we felt the terrifying thunder of hooves resonate under our feet. Mounted police were waving batons and, as the crowd poured into the square, we came face to face with a wall of shields and sticks. Charge after charge was launched, the police lashing out with furious, twisted faces. Batons connected with heads, blood poured. A lilting voice I I recognised as Manchanda’s was calling, ‘Don’t be provoked! Remain calm.’

A giant with a straggly, ginger beard had tripped and fallen backwards as he tried to push his way though the surrounding hedge into the centre of the square. He’d succeeded in forcing an opening, and then lay helpless as demonstrators used his stomach to leapfrog into the breach. I hesitated for a second then joined the others who were taking advantage of the man’s great belly to propel themselves into the green in front of the embassy. A woman, limbs akimbo, was beaten repeatedly between the legs. Atop the embassy building, marines with machine guns, were silhouetted against the sky. The Battle of Grosvenor Square was enjoined.

After the violence had subsided and a stand-off was achieved between ourselves and the police we made our way to the Union Tavern, drawn by the opportunity to hear Peggy Seeger and Ewan MacColl singing live.

In the downstairs bar we watched the TV, helpless with laughter, as Tariq Ali and Robin Blackburn whistled the Red Flag into a microphone at Hyde Park. Upstairs, Peggy and Ewan were singing the anthem of the movement. Peggy had arranged her many instruments on the floor in front of her music stool: guitar, ukulele, flute, drums, accordion.

“Far away, across the mountains,

Way beyond the sea’s eastern rim,

Lives a man who is father of the IndoChinese

people and his name is Ho Chi Minh

Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh, Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh... “

Downstairs, a Canadian woman with a Prince Valiant haircut was telling a story about Manchanda, while he gave a press conference in a side room. I recognised the man whose stomach I’d stepped on, Big Mike.

‘Manu was studying law at the Inns of Courts when the Duke of Edinburgh paid a visit. The Duke was going round greeting

students, most of them from overseas. “Where do you come from?” he asked them one by one. When he got to Manu, Manu said, “Hampstead.” ’

I leaned in, straining to hear the story above the music. ‘Quick as a flash, the Duke says, “What part of India is that?”’

The woman was gasping with mirth, ‘Guess what Manu said...

“What part of England is Greece? Oh, but you’re OK aren’t you? Didn’t you marry an English girl?” ’

At that first evening at the Union Tavern I was given a quick lesson on what a ‘Trot’ was - a Trotskyite - and was informed that they didn’t support national liberation movements because ‘peasants’ usually led them. Why would subsistence farmers join a socialist revolution that may collectivise their small land holdings? Neither did the ‘Trots' support the slogans ‘Victory to the NLF’ and ‘Long Live Ho Chi Minh.’

Chris described how Manchanda had anticipated a walkout over these issues from the inaugural meeting of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign in June 1966. He’d booked an alternative venue nearby so that comrades who walked out could get together quickly to form another organisation that did support the NLF and Ho Chi Minh. Chinese observers from the embassy and the Hsinhua news agency, the Vietnamese News Agency representatives, all the African Liberation Movement delegates who were in the pro-Chinese camp, including the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania,

SWAPO and ZANU, walked out together. The CPGB and other pro-Soviet groups remained in the Troskyite-dominated VSC.

After the demo an article by Mary McCarthy appeared in The Sunday Times and New York Review of Books. The woman who’d written The Group was taking sides, and had come down on what I had begun to think of as my side, my group. I remembered crying in the darkened cinema when the lesbian character in The Group killed herself.

‘Mr Manchanda, a former teacher, was an old-fashioned

classical Marxist,’ McCarthy wrote. ‘Like many of those men, he had a witty mind...”

‘What came out of our meeting with Mr

Manchanda, following on our meeting with Tariq Ali,

was a series of paradoxes...the style of Tariq Ali was

radical; the style of Mr Manchanda was modest petty

bourgeois, recalling the home lives of Marx, Lenin

and Trotsky himself. Maoist China, they say, is

hermetic, suspicious, hostile to foreigners, yet the

Maoist cell in Hampstead was open as the

Laundromat where Mr Manchanda had been doing his

smalls. Though we came from the bourgeois Press, we

were not treated as trespassers but simply as guests –

the reverse of what happened in Carlisle Street.x

‘This, too, perhaps a lesson in the

persuasiveness of non-violent techniques on the plane

of human relations, for the next afternoon, marching

up from the Embankment, when we came to the

crossroads of choice at Trafalgar Square, whether to

turn left with the Maoists to Grosvenor Square, I had

no real hesitation in making up my mind, and what

slight hesitation I had was purely journalistic...on

these issues I found myself agreeing with Mr

Manchanda: the main enemy is in Grosvenor Square;

march on him there...’

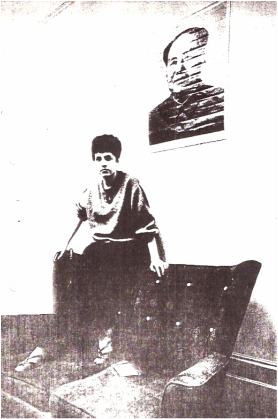

It wasn’t long before I became familiar with all the comrades, and the shabby rooms at Lisburne Road, the chaise longue, which Manu used as his bed, the heavy dresser, the cloth portraits of Marx, Engels, Stalin, Lenin and Chairman Mao and framed photograph of Claudia Jones.

I became detached from my past, like a snake shedding a skin, individuating from existing family and friends, feeling rage at all I knew who’d refused to move on with me. Having acquired the facility to name things, racism, sexism, capitalism, imperialism, there was no turning back. Naively, I wrote long, ranting letters to my parents, berating them for their racism, ignorance and refusal to acknowledge the dispossession of the indigenous people of Aoetearoa New Zealand which enabled them to call themselves ‘New Zealanders’ and lead privileged lives.

Of the group I’d joined and idealised, all of them knew more than I, all were braver, like perfect beings. It was a long time before I began to see them as flawed individuals or, in the case of one or two, actually deeply unpleasant characters.

For the moment, I loved all the comrades and took for granted that whatever faults became apparent as time went by, they all genuinely wanted to share the Earth fairly, stop war and imperialism, rid the world of super-exploitation and racism. I was swept up in the notion of human solidarity, progress and socialism. Hippies and pacifists were ridiculed. White

liberals were beneath contempt.

One evening, I’d turned up at Lisburne Road half an hour late to find a meeting already in progress. A man from the Campaign for Homosexual Equality was speaking about the persecution of gay people. Flabbergasted that this was being discussed, I felt my position as the only gay person in the RMLL closet was under threat. The body language of the listeners was tense; everybody was uptight except Manu, relaxed in the lotus position, making roll-ups with his cigarette machine. After the guy left, there was nervous laughter.

‘Why did you invite him?’ demanded one of the Mikes.

‘He’s a sincere comrade’ said Manchanda. ‘They’re getting organised.’

When everyone else had gone home, he asked me, ‘Where do you go, after our meetings?’ I told him the name of the woman I was seeing, who he knew was an out and proud lesbian. Had the CHE man had been invited especially for my benefit? Did Manu expected me to ‘out’ myself in the meeting? In front of all those conservative ‘revolutionaries,’ whose most progressive opinion on the subject was that gayness is an illness in need of treatment? Around that time, I heard many on the ‘left’ speak of homosexuality as ‘a bourgeois excrescence.’

After the coup within CARD, I’d given up going to their office. All my time, energy and spare cash went into the projects directed by Manchanda from 58 Lisburne Road. I began staying over, learning how to print from a gestetner machine and operate a cumbersome typesetting machine called a Varityper. Manu was generous in sharing practical and journalistic skills honed from his own experience which enabled people to gain confidence.

Eventually, Manu’s invitation to live with him at Lisburne Road seemed a wonderful opportunity to begin a meaningful existence. I didn’t hesitate. Revolutionary politics came way above and before the personal. I had a few years to go before I completely got the message: the personal is political. Meanwhile I was still busy making leaflets that read: ‘Class War, not Sex War!’

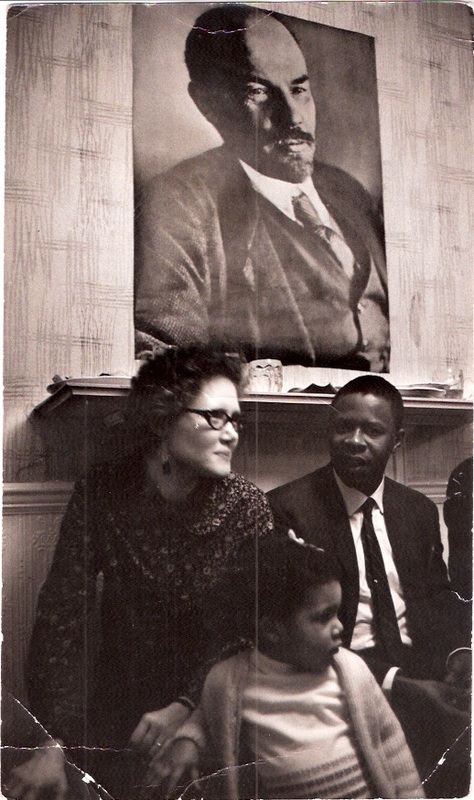

Manu was lonely, despite being surrounded with people most of the time and I came to appreciate that he was still missing Claudia both personally and politically. Who else shared so completely his revolutionary politics? Who else embodied such a rich experience of organising and analysing?

By the time I’d arrived on the scene, it was obvious that membership of the Communist Party of Great Britain was not an option for anyone interested in joining the anti-imperialist movement. As for theory, dialectical and historical materialism, political economy, surplus value, the dictatorship of the proletariat, the lot, I completely embraced, and, mostly, still do. We even had jokes: what do you get if you buy a pig for 10 kopeks and sell it for 12 kopeks? Answer: six months hard labour.

Manu educated me about the partition of India, the slave triangle, the Russian Revolution, and even the Dublin uprising. My grandmother had often spoken of seeing the Black and Tans coming over the hill, but as soon as I was wise enough to check the dates, I found she was deluded or confused, as her parents had already migrated from Ireland to New Zealand when she was born.

I devoured A People’s History of England, Ireland Her Own, Man’s Worldly Goods, Mao’s On Contradiction, and the rest. For the first time, I read Shelley’s words – ‘Rise Like Lions after slumber in unvanquishable number...yea are many, they are few...’

Membership of the inner core, the Revolutionary Marxist Leninist League, was not open and could only be acquired by working for some time in one of the ‘front’ groups such as Friends of China or the Britain Vietnam Solidarity Front. A period of candidate membership followed, and attainment of full acceptance felt like an achievement. According to Manu, he and Claudia had been aghast at how easy it was to join the Communist Party of Great Britain. Claudia used to make fun of the CPGB,. ‘All you have to do is fill in a form on the back of the Daily Worker (now Morning Star) and you could become a member.’

Mike and Helen were art students at Goldsmiths. Big Mike and his sister Chris were from Canada, who along with their respective spouses formed a bloc within the inner core of the RMLL; Roberta, who’d always arrive late for meetings, made us laugh when she said she’d ‘braved hardship and death’ to get to a meeting (it was raining, or she’d missed the bus); Ed was leader of the London Revolutionary Socialist Students Federation. He sulked when his partner, Barbara, ‘got it’ and he didn’t ‘get it’ during a study session on surplus value. He later split with us to form an Irish Liberation solidarity group, denouncing Manchanda for ‘crimes against Marxism-Leninism.’

Harpal and Maysel Brar, lecturers in law, soon broke away to form yet another tiny Maoist sect, having ‘denounced’ Manchanda for more such crimes. These centred on the creation of Bangladesh which Manu saw as a further partitioning of the subcontinent along religious/colonial lines. He identified Soviet and Indian meddling as a form of social imperialism. This was evidenced, he said, by the dismantling and taking to India of East Pakistan’s jute factories. But, in any case, on principle, he opposed all forms of partition.

Comrade N.M. Seedo, a writer from Minsk, lived on nuts and seeds. Was ‘Seedo’ her real name? At her flat overlooking Clissold Park she’d fashioned a three-piece suite from remaindered books covered with shawls. Her writing reminded me of Natalie Sarraute, only less intelligible. She was tiny with raisin eyes, white makeup, red lipstick and jet black hair. She wore a white fake fur coat, black leggings, and a beret at all times, even indoors.

In 1969, after ordering the carpet-bombing of Cambodia, the US President visited London, staying at Claridges Hotel. We set up the Hot Reception for Nixon Committee. The police corralled a section of the crowd outside his hotel. Seedo and I became caught up in that cordon of police horses and were kept there all night, tough on an elderly woman with a weak bladder.

I pleaded with the police to allow her to leave. But they kept making the circle of horses smaller and smaller until we were squeezed so tightly we were forced to stand.

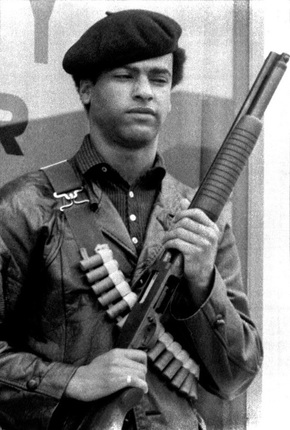

In solidarity with the Black Panthers, I remember marching to the U.S. embassy to support Huey Newton. A handful of us were accompanied by hundreds of police and as we approached the embassy we saw rows of black vans parked up in the side streets.

We heard the marchers approaching, shouting, banging drums, blowing whistles. Police on horses rushed past. As the demonstration reached the corner at Trafalgar Square, a group of running men and women with loud hailers worked the crowd, ‘Don’t be diverted. Follow the red banner to the US Embassy!’

Mary and I inserted ourselves into the swathe of bodies that peeled off in the direction of Grosvenor Square. Tall men on either side of me linked arms and I felt myself being lifted off the ground. All I could think about was staying alive in the crush. When we reached the US Embassy the police were waiting, riot shields poised. Horses were snorting and steaming and we felt the terrifying thunder of hooves resonate under our feet. Mounted police were waving batons and, as the crowd poured into the square, we came face to face with a wall of shields and sticks. Charge after charge was launched, the police lashing out with furious, twisted faces. Batons connected with heads, blood poured. A lilting voice I I recognised as Manchanda’s was calling, ‘Don’t be provoked! Remain calm.’

A giant with a straggly, ginger beard had tripped and fallen backwards as he tried to push his way though the surrounding hedge into the centre of the square. He’d succeeded in forcing an opening, and then lay helpless as demonstrators used his stomach to leapfrog into the breach. I hesitated for a second then joined the others who were taking advantage of the man’s great belly to propel themselves into the green in front of the embassy. A woman, limbs akimbo, was beaten repeatedly between the legs. Atop the embassy building, marines with machine guns, were silhouetted against the sky. The Battle of Grosvenor Square was enjoined.

After the violence had subsided and a stand-off was achieved between ourselves and the police we made our way to the Union Tavern, drawn by the opportunity to hear Peggy Seeger and Ewan MacColl singing live.

In the downstairs bar we watched the TV, helpless with laughter, as Tariq Ali and Robin Blackburn whistled the Red Flag into a microphone at Hyde Park. Upstairs, Peggy and Ewan were singing the anthem of the movement. Peggy had arranged her many instruments on the floor in front of her music stool: guitar, ukulele, flute, drums, accordion.

“Far away, across the mountains,

Way beyond the sea’s eastern rim,

Lives a man who is father of the IndoChinese

people and his name is Ho Chi Minh

Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh, Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh... “

Downstairs, a Canadian woman with a Prince Valiant haircut was telling a story about Manchanda, while he gave a press conference in a side room. I recognised the man whose stomach I’d stepped on, Big Mike.

‘Manu was studying law at the Inns of Courts when the Duke of Edinburgh paid a visit. The Duke was going round greeting

students, most of them from overseas. “Where do you come from?” he asked them one by one. When he got to Manu, Manu said, “Hampstead.” ’

I leaned in, straining to hear the story above the music. ‘Quick as a flash, the Duke says, “What part of India is that?”’

The woman was gasping with mirth, ‘Guess what Manu said...

“What part of England is Greece? Oh, but you’re OK aren’t you? Didn’t you marry an English girl?” ’

At that first evening at the Union Tavern I was given a quick lesson on what a ‘Trot’ was - a Trotskyite - and was informed that they didn’t support national liberation movements because ‘peasants’ usually led them. Why would subsistence farmers join a socialist revolution that may collectivise their small land holdings? Neither did the ‘Trots' support the slogans ‘Victory to the NLF’ and ‘Long Live Ho Chi Minh.’

Chris described how Manchanda had anticipated a walkout over these issues from the inaugural meeting of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign in June 1966. He’d booked an alternative venue nearby so that comrades who walked out could get together quickly to form another organisation that did support the NLF and Ho Chi Minh. Chinese observers from the embassy and the Hsinhua news agency, the Vietnamese News Agency representatives, all the African Liberation Movement delegates who were in the pro-Chinese camp, including the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania,

SWAPO and ZANU, walked out together. The CPGB and other pro-Soviet groups remained in the Troskyite-dominated VSC.

After the demo an article by Mary McCarthy appeared in The Sunday Times and New York Review of Books. The woman who’d written The Group was taking sides, and had come down on what I had begun to think of as my side, my group. I remembered crying in the darkened cinema when the lesbian character in The Group killed herself.

‘Mr Manchanda, a former teacher, was an old-fashioned

classical Marxist,’ McCarthy wrote. ‘Like many of those men, he had a witty mind...”

‘What came out of our meeting with Mr

Manchanda, following on our meeting with Tariq Ali,

was a series of paradoxes...the style of Tariq Ali was

radical; the style of Mr Manchanda was modest petty

bourgeois, recalling the home lives of Marx, Lenin

and Trotsky himself. Maoist China, they say, is

hermetic, suspicious, hostile to foreigners, yet the

Maoist cell in Hampstead was open as the

Laundromat where Mr Manchanda had been doing his

smalls. Though we came from the bourgeois Press, we

were not treated as trespassers but simply as guests –

the reverse of what happened in Carlisle Street.x

‘This, too, perhaps a lesson in the

persuasiveness of non-violent techniques on the plane

of human relations, for the next afternoon, marching

up from the Embankment, when we came to the

crossroads of choice at Trafalgar Square, whether to

turn left with the Maoists to Grosvenor Square, I had

no real hesitation in making up my mind, and what

slight hesitation I had was purely journalistic...on

these issues I found myself agreeing with Mr

Manchanda: the main enemy is in Grosvenor Square;

march on him there...’

It wasn’t long before I became familiar with all the comrades, and the shabby rooms at Lisburne Road, the chaise longue, which Manu used as his bed, the heavy dresser, the cloth portraits of Marx, Engels, Stalin, Lenin and Chairman Mao and framed photograph of Claudia Jones.

I became detached from my past, like a snake shedding a skin, individuating from existing family and friends, feeling rage at all I knew who’d refused to move on with me. Having acquired the facility to name things, racism, sexism, capitalism, imperialism, there was no turning back. Naively, I wrote long, ranting letters to my parents, berating them for their racism, ignorance and refusal to acknowledge the dispossession of the indigenous people of Aoetearoa New Zealand which enabled them to call themselves ‘New Zealanders’ and lead privileged lives.

Of the group I’d joined and idealised, all of them knew more than I, all were braver, like perfect beings. It was a long time before I began to see them as flawed individuals or, in the case of one or two, actually deeply unpleasant characters.

For the moment, I loved all the comrades and took for granted that whatever faults became apparent as time went by, they all genuinely wanted to share the Earth fairly, stop war and imperialism, rid the world of super-exploitation and racism. I was swept up in the notion of human solidarity, progress and socialism. Hippies and pacifists were ridiculed. White

liberals were beneath contempt.

One evening, I’d turned up at Lisburne Road half an hour late to find a meeting already in progress. A man from the Campaign for Homosexual Equality was speaking about the persecution of gay people. Flabbergasted that this was being discussed, I felt my position as the only gay person in the RMLL closet was under threat. The body language of the listeners was tense; everybody was uptight except Manu, relaxed in the lotus position, making roll-ups with his cigarette machine. After the guy left, there was nervous laughter.

‘Why did you invite him?’ demanded one of the Mikes.

‘He’s a sincere comrade’ said Manchanda. ‘They’re getting organised.’

When everyone else had gone home, he asked me, ‘Where do you go, after our meetings?’ I told him the name of the woman I was seeing, who he knew was an out and proud lesbian. Had the CHE man had been invited especially for my benefit? Did Manu expected me to ‘out’ myself in the meeting? In front of all those conservative ‘revolutionaries,’ whose most progressive opinion on the subject was that gayness is an illness in need of treatment? Around that time, I heard many on the ‘left’ speak of homosexuality as ‘a bourgeois excrescence.’

After the coup within CARD, I’d given up going to their office. All my time, energy and spare cash went into the projects directed by Manchanda from 58 Lisburne Road. I began staying over, learning how to print from a gestetner machine and operate a cumbersome typesetting machine called a Varityper. Manu was generous in sharing practical and journalistic skills honed from his own experience which enabled people to gain confidence.

Eventually, Manu’s invitation to live with him at Lisburne Road seemed a wonderful opportunity to begin a meaningful existence. I didn’t hesitate. Revolutionary politics came way above and before the personal. I had a few years to go before I completely got the message: the personal is political. Meanwhile I was still busy making leaflets that read: ‘Class War, not Sex War!’

Manu was lonely, despite being surrounded with people most of the time and I came to appreciate that he was still missing Claudia both personally and politically. Who else shared so completely his revolutionary politics? Who else embodied such a rich experience of organising and analysing?

By the time I’d arrived on the scene, it was obvious that membership of the Communist Party of Great Britain was not an option for anyone interested in joining the anti-imperialist movement. As for theory, dialectical and historical materialism, political economy, surplus value, the dictatorship of the proletariat, the lot, I completely embraced, and, mostly, still do. We even had jokes: what do you get if you buy a pig for 10 kopeks and sell it for 12 kopeks? Answer: six months hard labour.

Manu educated me about the partition of India, the slave triangle, the Russian Revolution, and even the Dublin uprising. My grandmother had often spoken of seeing the Black and Tans coming over the hill, but as soon as I was wise enough to check the dates, I found she was deluded or confused, as her parents had already migrated from Ireland to New Zealand when she was born.

I devoured A People’s History of England, Ireland Her Own, Man’s Worldly Goods, Mao’s On Contradiction, and the rest. For the first time, I read Shelley’s words – ‘Rise Like Lions after slumber in unvanquishable number...yea are many, they are few...’

Membership of the inner core, the Revolutionary Marxist Leninist League, was not open and could only be acquired by working for some time in one of the ‘front’ groups such as Friends of China or the Britain Vietnam Solidarity Front. A period of candidate membership followed, and attainment of full acceptance felt like an achievement. According to Manu, he and Claudia had been aghast at how easy it was to join the Communist Party of Great Britain. Claudia used to make fun of the CPGB,. ‘All you have to do is fill in a form on the back of the Daily Worker (now Morning Star) and you could become a member.’

Mike and Helen were art students at Goldsmiths. Big Mike and his sister Chris were from Canada, who along with their respective spouses formed a bloc within the inner core of the RMLL; Roberta, who’d always arrive late for meetings, made us laugh when she said she’d ‘braved hardship and death’ to get to a meeting (it was raining, or she’d missed the bus); Ed was leader of the London Revolutionary Socialist Students Federation. He sulked when his partner, Barbara, ‘got it’ and he didn’t ‘get it’ during a study session on surplus value. He later split with us to form an Irish Liberation solidarity group, denouncing Manchanda for ‘crimes against Marxism-Leninism.’

Harpal and Maysel Brar, lecturers in law, soon broke away to form yet another tiny Maoist sect, having ‘denounced’ Manchanda for more such crimes. These centred on the creation of Bangladesh which Manu saw as a further partitioning of the subcontinent along religious/colonial lines. He identified Soviet and Indian meddling as a form of social imperialism. This was evidenced, he said, by the dismantling and taking to India of East Pakistan’s jute factories. But, in any case, on principle, he opposed all forms of partition.

Comrade N.M. Seedo, a writer from Minsk, lived on nuts and seeds. Was ‘Seedo’ her real name? At her flat overlooking Clissold Park she’d fashioned a three-piece suite from remaindered books covered with shawls. Her writing reminded me of Natalie Sarraute, only less intelligible. She was tiny with raisin eyes, white makeup, red lipstick and jet black hair. She wore a white fake fur coat, black leggings, and a beret at all times, even indoors.

In 1969, after ordering the carpet-bombing of Cambodia, the US President visited London, staying at Claridges Hotel. We set up the Hot Reception for Nixon Committee. The police corralled a section of the crowd outside his hotel. Seedo and I became caught up in that cordon of police horses and were kept there all night, tough on an elderly woman with a weak bladder.

I pleaded with the police to allow her to leave. But they kept making the circle of horses smaller and smaller until we were squeezed so tightly we were forced to stand.

In solidarity with the Black Panthers, I remember marching to the U.S. embassy to support Huey Newton. A handful of us were accompanied by hundreds of police and as we approached the embassy we saw rows of black vans parked up in the side streets.

Manu, one of the Mikes and I went to Algiers for an international conference in support of the Palestine Liberation

Organisation. We spent Christmas of ‘69 in Paris before flying south in a corkscrewing plane. As the aircraft buffeted, nosedived and turned upside, the comrades continued their bright chatter as if nothing unusual was going on. A joke was made about Vuse Make’s bulk. [Vusumzi L. Make, Chief Representative of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC)]. Someone sent Vuse a note purportedly from the pilot asking him to move to a different part of the plane as his weight was making the plane lopsided and difficult to fly.

The conference opening was delayed for an hour when Tom Murray and Matt Lygate of the Workers’ Party of Scotland refused to sit behind a nameplate that read ‘United Kingdom.’ Arafat waited patiently to make his keynote speech, chatting and sipping water. Eventually, a wooden board was produced with the word 'Scotland' scored into it.

Every seat was equipped with headphones. A phalanx of translators sat in a glass box at the back. Arafat’s speech lasted nearly two hours and at the end of it, everyone in the hall knew the history of Palestinian dispossession and resistance.

I was badly in need of educating. For years, I had no idea that the State of Israel had not existed before 1948 and that 750,000 Palestinians had been forcibly removed from their homes and land to make way for it, or that in 1967 in a blitzkrieg that lasted six days they’d lost the remaining 22 per cent of Palestine. The inalienable right of return of refugees, normally upheld by international law, has never been implemented in the case of the Palestinian people.

Louis Eakes of the Young Liberals, a courageous campaigner for gay rights as well as for the cause of the Palestinian people was at the conference. Manu was co-opted onto the drafting committee for the declaration to be issued that would proclaim international solidarity with the Palestinians and set out their political demands for national sovereignty and self-determination, including the right of return to their homeland.

Our beachside hotel was formerly Tshombe’s place of incarceration, located on cliffs with the sea beating below.

As with the sumptuous food served at banquets we attended at the Chinese Embassy, the food at the PLO conference was

spectacular. Every meal was a banquet with wine flowing. Eldridge Cleaver and his many wives were at the main table with Yasser Arafat and other international figures.

When it was my turn to give a report about solidarity work in London to support Black Panthers in prison, I said ‘Huey Long,’ by mistake, instead of ‘Huey Newton.’ Everyone laughed. I felt a fool but was comforted by an American comrade from the Bay Area Revolutionary Union. Her comrade, Leibel, had dressed as a woman to throw the FBI off the scent, and they'd arrived at the conference after swapping planes several times.

The American comrades chose exciting names for their groups: Verencemos and The Weathermen, from the Dylan line – ‘you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.’

Our wedding, soon after we returned from Algeria, was an international gathering. I wore a mini-skirt to the registry office in Hampstead and a sari to the party afterwards. Photographs were taken by Romano Cagnoni, a brilliant photo-journalist, as a generous wedding present . Our friend and comrade, Richard Gibson and his partner, Sarah, opened their house in Stamford Bridge for a great party in the evening.

Organisation. We spent Christmas of ‘69 in Paris before flying south in a corkscrewing plane. As the aircraft buffeted, nosedived and turned upside, the comrades continued their bright chatter as if nothing unusual was going on. A joke was made about Vuse Make’s bulk. [Vusumzi L. Make, Chief Representative of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC)]. Someone sent Vuse a note purportedly from the pilot asking him to move to a different part of the plane as his weight was making the plane lopsided and difficult to fly.

The conference opening was delayed for an hour when Tom Murray and Matt Lygate of the Workers’ Party of Scotland refused to sit behind a nameplate that read ‘United Kingdom.’ Arafat waited patiently to make his keynote speech, chatting and sipping water. Eventually, a wooden board was produced with the word 'Scotland' scored into it.

Every seat was equipped with headphones. A phalanx of translators sat in a glass box at the back. Arafat’s speech lasted nearly two hours and at the end of it, everyone in the hall knew the history of Palestinian dispossession and resistance.

I was badly in need of educating. For years, I had no idea that the State of Israel had not existed before 1948 and that 750,000 Palestinians had been forcibly removed from their homes and land to make way for it, or that in 1967 in a blitzkrieg that lasted six days they’d lost the remaining 22 per cent of Palestine. The inalienable right of return of refugees, normally upheld by international law, has never been implemented in the case of the Palestinian people.

Louis Eakes of the Young Liberals, a courageous campaigner for gay rights as well as for the cause of the Palestinian people was at the conference. Manu was co-opted onto the drafting committee for the declaration to be issued that would proclaim international solidarity with the Palestinians and set out their political demands for national sovereignty and self-determination, including the right of return to their homeland.

Our beachside hotel was formerly Tshombe’s place of incarceration, located on cliffs with the sea beating below.

As with the sumptuous food served at banquets we attended at the Chinese Embassy, the food at the PLO conference was

spectacular. Every meal was a banquet with wine flowing. Eldridge Cleaver and his many wives were at the main table with Yasser Arafat and other international figures.

When it was my turn to give a report about solidarity work in London to support Black Panthers in prison, I said ‘Huey Long,’ by mistake, instead of ‘Huey Newton.’ Everyone laughed. I felt a fool but was comforted by an American comrade from the Bay Area Revolutionary Union. Her comrade, Leibel, had dressed as a woman to throw the FBI off the scent, and they'd arrived at the conference after swapping planes several times.

The American comrades chose exciting names for their groups: Verencemos and The Weathermen, from the Dylan line – ‘you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.’

Our wedding, soon after we returned from Algeria, was an international gathering. I wore a mini-skirt to the registry office in Hampstead and a sari to the party afterwards. Photographs were taken by Romano Cagnoni, a brilliant photo-journalist, as a generous wedding present . Our friend and comrade, Richard Gibson and his partner, Sarah, opened their house in Stamford Bridge for a great party in the evening.

Richard was a multi-lingual, African-American journalist who’d become stateless through helping Robert F. Williams to escape to Cuba. Williams, a member of the Black Panther Party, was accused of kidnapping a Klanswoman who’d taken shelter in his car during a KKK attack. Despite her affiliation with the KKK she gave evidence that should have cleared Williams’ name but the FBI still pursued him on the kidnapping charge.

The comrades had decorated the walls of Richard and Sarah's house with pictures of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin and Mao and they presented us with a leather-bound set of the complete works of Joseph Stalin, printed by the People’s Publishing House, Peking. My brother played the piano and I sang.

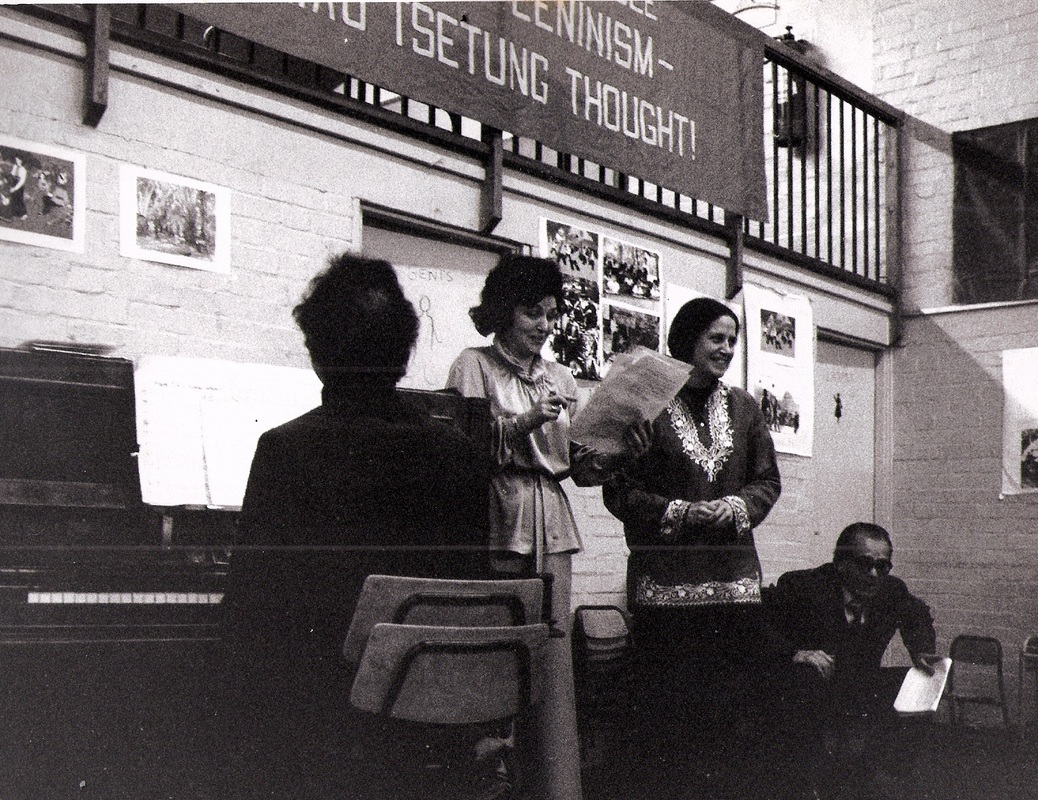

My piano-playing brother, Bill, was a member of the RMLL and joined a group of revolutionary students at the Royal Academy of Music. He was often called upon to accompany the singing of revolutionary songs and a few years later, played The East is Red at the funeral of Olive Morris.

The comrades had decorated the walls of Richard and Sarah's house with pictures of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin and Mao and they presented us with a leather-bound set of the complete works of Joseph Stalin, printed by the People’s Publishing House, Peking. My brother played the piano and I sang.

My piano-playing brother, Bill, was a member of the RMLL and joined a group of revolutionary students at the Royal Academy of Music. He was often called upon to accompany the singing of revolutionary songs and a few years later, played The East is Red at the funeral of Olive Morris.

Among the guests were representatives of the Palestine Liberation Organisation, the Pan African Congress, Zimbabwe African National Union, and freedom fighters from Mozambique, South West Africa and elsewhere.

Manu’s sister and nieces had dressed me in a sari that kept unraveling. His family was hugely welcoming and I quickly became close to them, even those who lived in India. His sister Raj visited London frequently. His nieces, Asha and Meena adored their uncle who had looked after them for a while as young teenagers after they arrived in London expecting to be met by their father, who had tragically passed away while they were on the plane. We visited India several times and spent wonderful times with his family, friends and comrades.

Manu’s sister and nieces had dressed me in a sari that kept unraveling. His family was hugely welcoming and I quickly became close to them, even those who lived in India. His sister Raj visited London frequently. His nieces, Asha and Meena adored their uncle who had looked after them for a while as young teenagers after they arrived in London expecting to be met by their father, who had tragically passed away while they were on the plane. We visited India several times and spent wonderful times with his family, friends and comrades.

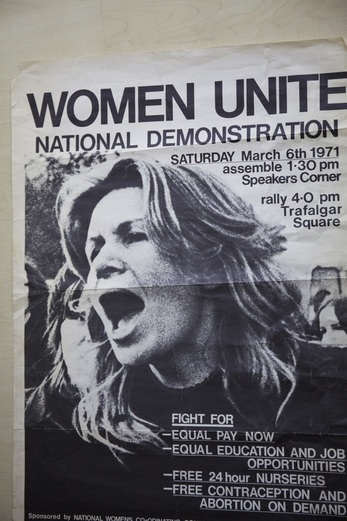

My first inkling of the Women’s Liberation Movement came from reading Maoist-inclined American journals such as Red Papers and The Guardian that published articles by Roxanne Dunbar and Charlotte Bunch. International papers and pamphlets were constantly dropping through the letterbox at Lisburne Road, including The Crusader published in Peking by Robert F. Williams on fine, airmail, tissue-paper, the Daily Hsinhua Report, Peking Review, Women of China and journals of the African Liberation Movements and Communist Party of India (M-L).

In tune with the general atmosphere of liberation and change, British women had begun forming consciousness-raising groups, many within the framework of the Women’s Liberation Workshop. After the wedding, Manu started reading my unopened copy of The Dialectics of Sex by Shulamith Firestone (1970), making his own underlinings and notes in the margins, rendering the book even more difficult to read.

Claudia Jones had been a feminist and, if it was good enough for her, our women comrades had better get with the programme.

Manu reminded us that Claudia was deported from the US over her article commemorating International Women’s Day.

‘Super exploitation’ was an expression with which I became familiar, as applied by Claudia and Manchanda to Black women’s labour and to the world at large in terms of colonial exploitation. An article published on International Women’s Day, 1951, had triggered Claudia’s arrest by the FBI. Her writings on race and gender pre-dated the second wave of the Women’s

Liberation Movement by 20 years.

The comrades tasked me with writing a leaflet about International Women's Day. Everything I read while researching the piece patronisingly described the event as being inspired by a ‘match girls’ strike.

In Vietnam, women’s brigades were marvellously proficient at shooting down American planes. A visiting women’s delegation presented us with an engraved vase made of metal from a plane downed by women. But still our comrades were not wholly persuaded about the Women’s Liberation Movement.

‘Why would we want to join those petit bourgeois gits,’

Comrade Chris wanted to know. ‘They’re just a bunch of man-haters.’

‘Women are exploited and oppressed. Women’s Liberation is part of the struggle,’ Manu argued. ‘Read Engels, Origin of the

Family, Private Property and the State.’

Although Engels’ historical approach explained a lot, I didn’t see the lives of my mother, my aunts, or my grandmother reflected in the Marxist classics or in the theoretical writings of feminist writers such as Firestone. A friend of mine had died from blood poisoning after a back street termination two years before the 1967 Abortion Act was passed. In my grief, I’d raged against ‘the system’ but had no name for it. Now, the Women’s Liberation Movement was shining a spotlight on patriarchy. The phenomenon had been named before, but naming alone had not succeeded in spreading consciousness like wildfire. The unrelenting mockery of the WLM by the mass media made everyone aware of ‘women’s lib,' as they sneeringly called our liberation movement.

Everywhere I looked I saw women’s powerlessness, lives of domestic drudgery and boredom, lack of education, low self-esteem. I remembered the small-town bitchery, lack of solidarity between women and suppression of women’s talents and potential within my own family. I was attracted to the notion of liberation in relation to women, which expressed a link with the national liberation movements. The outraged cries of the male-dominated press, the disdainful attitude of the judiciary, educational and cultural establishment all helped to fuel the movement. Arguments about the ‘male wage’ surfaced in the unions; gender discrimination could no longer be ignored.

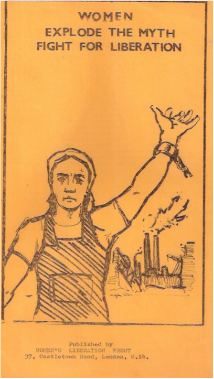

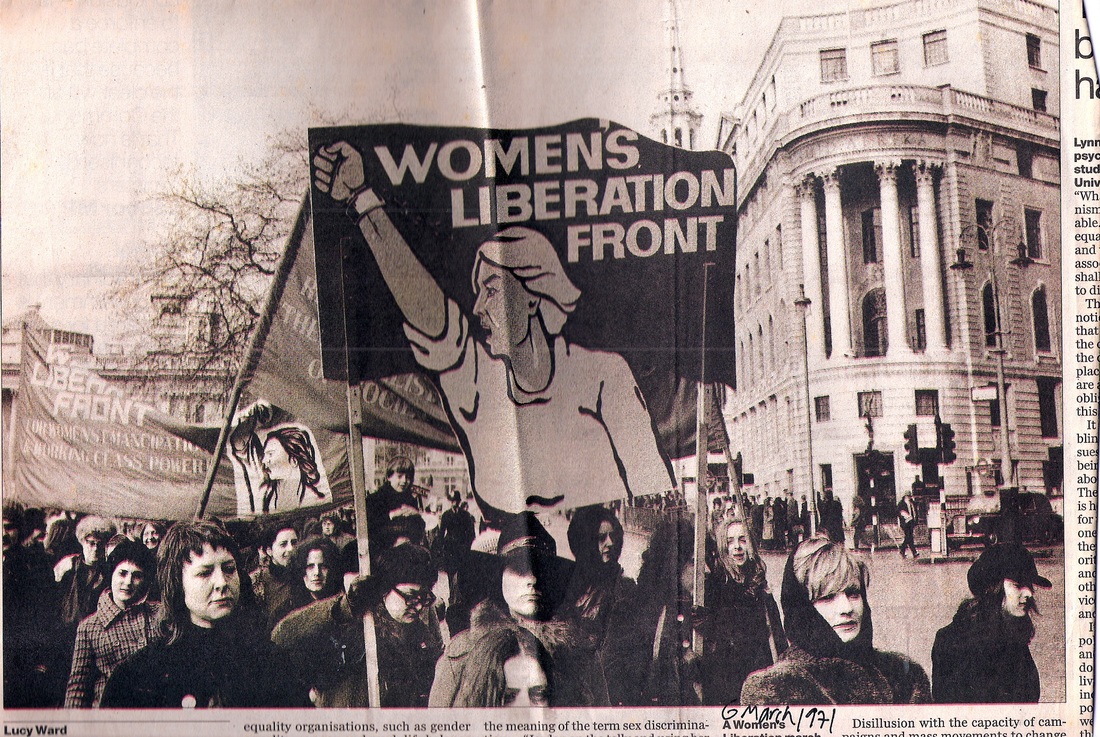

At Manu’s insistence, Chris and I attended the preparatory meetings for the first national Women’s Liberation conference at Ruskin College, Oxford, in 1970. With trade union women we set up the Women’s Equal Rights Committee – a 'broad front' – leftist terminology for an organisation the masses can join, but is usually controlled by the vanguard cognoscenti. For women who shared our international liberationist outlook, the RMLL created the Women’s Liberation Front.

Chris, a teacher, and I brought to these preparatory meetings the proposal that aiming for women's right to equal education should form one of the founding principles of the WLM. We researched and wrote about the situation intensively; I accessed statistics from the House of Commons library by claiming the information was requested by a Labour MP I was working for at the time, narrowly escaping being sacked. This work culminated in the adoption of the second of the movement's four original demands: Equal Education and Work Opportunities.

A unique meeting organised by the Women's Liberation Front was held at the Regent Street Polytechnic at which there were women speakers from Vietnam (Lin Qui), Palestine (Leila Mantoura) and Azania (Elizabeth Sibeko).

I recently found a leaflet advertising another meeting entitled ‘Women with Guns’, dating from around the same time. Peggy Seeger, Buff Orpington and other women musicians performed at gatherings organised by the Women’s Liberation Front at the Camden Studios.Our Turkish women comrades made a massive banner depicting a woman raising her fist with broken shackles.

In tune with the general atmosphere of liberation and change, British women had begun forming consciousness-raising groups, many within the framework of the Women’s Liberation Workshop. After the wedding, Manu started reading my unopened copy of The Dialectics of Sex by Shulamith Firestone (1970), making his own underlinings and notes in the margins, rendering the book even more difficult to read.

Claudia Jones had been a feminist and, if it was good enough for her, our women comrades had better get with the programme.

Manu reminded us that Claudia was deported from the US over her article commemorating International Women’s Day.

‘Super exploitation’ was an expression with which I became familiar, as applied by Claudia and Manchanda to Black women’s labour and to the world at large in terms of colonial exploitation. An article published on International Women’s Day, 1951, had triggered Claudia’s arrest by the FBI. Her writings on race and gender pre-dated the second wave of the Women’s

Liberation Movement by 20 years.

The comrades tasked me with writing a leaflet about International Women's Day. Everything I read while researching the piece patronisingly described the event as being inspired by a ‘match girls’ strike.

In Vietnam, women’s brigades were marvellously proficient at shooting down American planes. A visiting women’s delegation presented us with an engraved vase made of metal from a plane downed by women. But still our comrades were not wholly persuaded about the Women’s Liberation Movement.

‘Why would we want to join those petit bourgeois gits,’

Comrade Chris wanted to know. ‘They’re just a bunch of man-haters.’

‘Women are exploited and oppressed. Women’s Liberation is part of the struggle,’ Manu argued. ‘Read Engels, Origin of the

Family, Private Property and the State.’

Although Engels’ historical approach explained a lot, I didn’t see the lives of my mother, my aunts, or my grandmother reflected in the Marxist classics or in the theoretical writings of feminist writers such as Firestone. A friend of mine had died from blood poisoning after a back street termination two years before the 1967 Abortion Act was passed. In my grief, I’d raged against ‘the system’ but had no name for it. Now, the Women’s Liberation Movement was shining a spotlight on patriarchy. The phenomenon had been named before, but naming alone had not succeeded in spreading consciousness like wildfire. The unrelenting mockery of the WLM by the mass media made everyone aware of ‘women’s lib,' as they sneeringly called our liberation movement.

Everywhere I looked I saw women’s powerlessness, lives of domestic drudgery and boredom, lack of education, low self-esteem. I remembered the small-town bitchery, lack of solidarity between women and suppression of women’s talents and potential within my own family. I was attracted to the notion of liberation in relation to women, which expressed a link with the national liberation movements. The outraged cries of the male-dominated press, the disdainful attitude of the judiciary, educational and cultural establishment all helped to fuel the movement. Arguments about the ‘male wage’ surfaced in the unions; gender discrimination could no longer be ignored.

At Manu’s insistence, Chris and I attended the preparatory meetings for the first national Women’s Liberation conference at Ruskin College, Oxford, in 1970. With trade union women we set up the Women’s Equal Rights Committee – a 'broad front' – leftist terminology for an organisation the masses can join, but is usually controlled by the vanguard cognoscenti. For women who shared our international liberationist outlook, the RMLL created the Women’s Liberation Front.

Chris, a teacher, and I brought to these preparatory meetings the proposal that aiming for women's right to equal education should form one of the founding principles of the WLM. We researched and wrote about the situation intensively; I accessed statistics from the House of Commons library by claiming the information was requested by a Labour MP I was working for at the time, narrowly escaping being sacked. This work culminated in the adoption of the second of the movement's four original demands: Equal Education and Work Opportunities.

A unique meeting organised by the Women's Liberation Front was held at the Regent Street Polytechnic at which there were women speakers from Vietnam (Lin Qui), Palestine (Leila Mantoura) and Azania (Elizabeth Sibeko).

I recently found a leaflet advertising another meeting entitled ‘Women with Guns’, dating from around the same time. Peggy Seeger, Buff Orpington and other women musicians performed at gatherings organised by the Women’s Liberation Front at the Camden Studios.Our Turkish women comrades made a massive banner depicting a woman raising her fist with broken shackles.

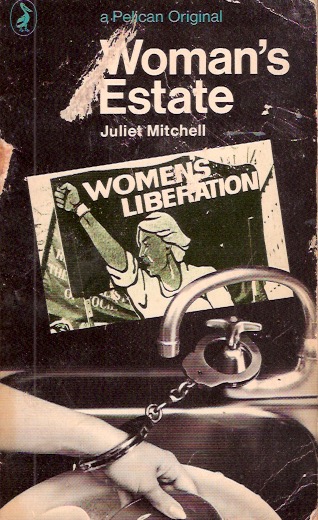

Juliet Mitchell later appropriated the image for the cover of her book Women’s Estate (1971) without acknowledgement. Inside she alleged of Maoist women, ‘sweetly, they call their leader, “Man,”’ and referred to Manchanda as ‘the Chairman Mao of Britain.’

A comrade from Zimbabwe, Eileen, came with us to Oxford. In the bathroom, a woman came over and grabbed a handful of her hair. ‘Ooh, it’s just like pubic hair,’ she exclaimed. Eileen calmly carried on washing her hands, running the water between her fingers and splashing her face.

‘Are you all right?’ I asked her.

‘Oh, you don’t have to worry about me,’ she said, ‘I’ve had worse.’

‘But I shouldn’t have put you in this position.’

‘On the contrary, I’m glad I came. It’s been interesting.’

I’d persuaded her to accompany me imagining that, if she addressed the conference, the women gathered there would embrace the idea of international solidarity. She wasn’t even called to speak, one of the few Black women at the event, and a very experienced organiser of the women’s movement in Zimbabwe.

Roberta and I volunteered to help transcribe the speeches at Ruskin and worked hard on tapes and notes, producing reams of interesting material, verbatim testimonies of women from dozens of different groups around the country as well as individuals with personal stories. When I delivered the transcript to the home of the well-known feminist writer who’d undertaken to publish the proceedings in a book, I was amazed by the grandness of her surroundings: the Ming vases and leopard skin rugs. ‘Just leave it over there,’ she said, apparently irritated by my intrusion. She had her feet up on a luxurious sofa and was sipping wine with a bunch of friends, recognisable faces from New Left Review.

At subsequent Women’s Liberation Workshop meetings, I kept asking when the transcript was going to appear in book form. But as far as I know nothing ever came of the book project, and I wondered what had become of the transcript. In 2014 I read about the Women's Library's move to the London School of Economics which referred to items included in the collection. 'Flimsy-typed pages are the only original surviving records of the first UK Women's Liberation Conference, held at Ruskin College in 1970, which voted for equal pay and education, free contraception and abortion on demand, and 24-hour state nurseries so that any woman could return to work.' [Maev Kennedy, The Guardian, 10 March 2014.]

My first experience of public speaking was delivering a paper that Manu and I had written together. We borrowed from a pamphlet that had belonged to Claudia that consisted of American feminist writings on sexist language such as ‘chairman’ when referring to women and the misogynist teachings of various religions. As I’d never read any scriptures, this was the first I’d heard of the ‘thanks, god, for not creating me a woman’ tendency in Judeao-Christianity.

Was it Leeds University where I’d made my speaking debut? Men were still being admitted to women’s liberation meetings although Manu never attended. Chris was going up and down between the rows of students in the tiered lecture hall distributing papers that I imagined were our usual Revolutionary Socialist Student Federation bumpf.

‘Although religion doesn’t have the grip on women’s lives it held a century ago,’ I said into the mic, ‘its roots still go deep into our culture, and its conception of a woman’s place forms a large part of the unconscious thinking even of non-religious people. All major religions hold women to be a sort of necessary evil...’

The audience was behaving oddly, their lips moving in synch with mine, a low hum became a drone, then a chorus. They were reading my speech along with me. Chris had handed out the transcript of my speech. My voice dried up and I wanted to disappear. Then I got angry and suddenly found my own voice rather than following the script.

Before the Skegness Women’s Liberation Conference, Chris MacKinnon and I met with Juliet Mitchell, Lois Graessle, Janet Hadley and others to put forward an idea that might solve to the problem of larger groups (code-name for Trots) dominating the movement. Our solution was to rotate the venue and chairing of each national conference. Every group would have equal access by a system of pooling resources. The host group would edit an issue of the magazine ‘Women’s Struggle.’

This would give a tremendous boost to smaller groups. Imagine hundreds of women turning up in a small town for such a conference! The women from the workshop accepted this plan. It never came to pass, only one issue of the paper was brought out. Maoists became persona non grata in the Women’s Movement after the debacle in Skegness when Harpal Brar jumped onto the stage. In any case, by time the conference came round, Manu and I had been expelled from the Women’s Liberation Front and all the other ‘fronts.’

A comrade from Zimbabwe, Eileen, came with us to Oxford. In the bathroom, a woman came over and grabbed a handful of her hair. ‘Ooh, it’s just like pubic hair,’ she exclaimed. Eileen calmly carried on washing her hands, running the water between her fingers and splashing her face.

‘Are you all right?’ I asked her.

‘Oh, you don’t have to worry about me,’ she said, ‘I’ve had worse.’

‘But I shouldn’t have put you in this position.’

‘On the contrary, I’m glad I came. It’s been interesting.’

I’d persuaded her to accompany me imagining that, if she addressed the conference, the women gathered there would embrace the idea of international solidarity. She wasn’t even called to speak, one of the few Black women at the event, and a very experienced organiser of the women’s movement in Zimbabwe.

Roberta and I volunteered to help transcribe the speeches at Ruskin and worked hard on tapes and notes, producing reams of interesting material, verbatim testimonies of women from dozens of different groups around the country as well as individuals with personal stories. When I delivered the transcript to the home of the well-known feminist writer who’d undertaken to publish the proceedings in a book, I was amazed by the grandness of her surroundings: the Ming vases and leopard skin rugs. ‘Just leave it over there,’ she said, apparently irritated by my intrusion. She had her feet up on a luxurious sofa and was sipping wine with a bunch of friends, recognisable faces from New Left Review.

At subsequent Women’s Liberation Workshop meetings, I kept asking when the transcript was going to appear in book form. But as far as I know nothing ever came of the book project, and I wondered what had become of the transcript. In 2014 I read about the Women's Library's move to the London School of Economics which referred to items included in the collection. 'Flimsy-typed pages are the only original surviving records of the first UK Women's Liberation Conference, held at Ruskin College in 1970, which voted for equal pay and education, free contraception and abortion on demand, and 24-hour state nurseries so that any woman could return to work.' [Maev Kennedy, The Guardian, 10 March 2014.]

My first experience of public speaking was delivering a paper that Manu and I had written together. We borrowed from a pamphlet that had belonged to Claudia that consisted of American feminist writings on sexist language such as ‘chairman’ when referring to women and the misogynist teachings of various religions. As I’d never read any scriptures, this was the first I’d heard of the ‘thanks, god, for not creating me a woman’ tendency in Judeao-Christianity.

Was it Leeds University where I’d made my speaking debut? Men were still being admitted to women’s liberation meetings although Manu never attended. Chris was going up and down between the rows of students in the tiered lecture hall distributing papers that I imagined were our usual Revolutionary Socialist Student Federation bumpf.

‘Although religion doesn’t have the grip on women’s lives it held a century ago,’ I said into the mic, ‘its roots still go deep into our culture, and its conception of a woman’s place forms a large part of the unconscious thinking even of non-religious people. All major religions hold women to be a sort of necessary evil...’

The audience was behaving oddly, their lips moving in synch with mine, a low hum became a drone, then a chorus. They were reading my speech along with me. Chris had handed out the transcript of my speech. My voice dried up and I wanted to disappear. Then I got angry and suddenly found my own voice rather than following the script.

Before the Skegness Women’s Liberation Conference, Chris MacKinnon and I met with Juliet Mitchell, Lois Graessle, Janet Hadley and others to put forward an idea that might solve to the problem of larger groups (code-name for Trots) dominating the movement. Our solution was to rotate the venue and chairing of each national conference. Every group would have equal access by a system of pooling resources. The host group would edit an issue of the magazine ‘Women’s Struggle.’

This would give a tremendous boost to smaller groups. Imagine hundreds of women turning up in a small town for such a conference! The women from the workshop accepted this plan. It never came to pass, only one issue of the paper was brought out. Maoists became persona non grata in the Women’s Movement after the debacle in Skegness when Harpal Brar jumped onto the stage. In any case, by time the conference came round, Manu and I had been expelled from the Women’s Liberation Front and all the other ‘fronts.’

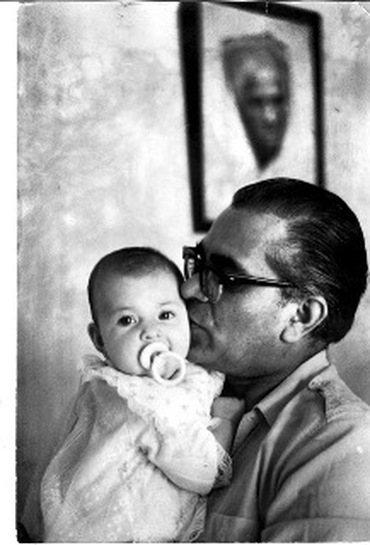

Our baby, born in December 1970, was named after Claudia Jones but we mostly called her Chu Chu. Manu undertook to do the major part of the childcare after I went back to work. He bottle-fed her as he conducted meetings. In the middle of a discussion, he changed her nappy on the chaise longue. Whenever I did it, he would undo the safety pin and re-do it the correct way.

The comrades presented us with a red plastic carrycot. Manu found a broken pushchair on a skip and we used that for wheels. The back of the chair wouldn’t stay upright, so we kept it flat and placed the carrycot on top.

‘The best support we can give the Vietnamese people is to have a revolution here,’ Comrade Chris asserted.

‘Have a little humility, comrades,’ pleaded Manu, rocking the baby on his knee. ‘Do you think the British working class is going to make a revolution any time soon? Stop all this arrogant nonsense that the British working class is the most advanced in the world. They’re the most backward in the world, the most racist in the world. The British working class benefits from imperialism every day.’

Comrade Chris flounced out of the room and, as she attempted to slam the door, her handbag became entrammeled and she was forced to return, which I found very funny. Laughter soured my relationship with Comrade Chris.

The comrades were becoming impatient, tempers fraying. We were in a hurry to make the revolution happen, ever waiting for the proletariat to kick into action. Surely the revolution was just around the corner, like the next bus?

For the first six years of Chu Chu’s life, we lived in the ground floor flat at 58 Lisburne Road in Hampstead, the place where Claudia Jones died on Christmas Day, 1964. As I write, campaigners are still petitioning the London Borough of Camden to place a blue plaque on the house. Had Claudia spent her last hours reclining on the same battered chaise longue upon which Manu rested and worked as long as we lived there? Every day I’d carry the baby upstairs to be washed in the

bathroom we shared with the family living on the upper floors. There was no lock on the door and where the lock should have been was an eye-sized hole, which the kids liked to peek through while we were taking baths. Our lavatory was in the garden outside the back door.

We became used to the white van with cables and aerials protruding from its roof that was permanently parked in Lisburne Road.

‘Special branch,’ Manu said. Once, when we were on a bus on the way to a demonstration, Manu mischievously asked the

conductor to collect our fares from two men who’d been clumsily tailing us. They paid up. I found it difficult to comprehend why our puny efforts caused so much concern to the authorities when everything we did was within the law and totally transparent..

‘You can go down to Speakers’ Corner and let off as much steam as you like,’ Manu explained, ‘and the nice, docile policemen will stand by, smiling. But if you challenge the state directly and start to turn public opinion about the war, that has to be quashed.’

He didn’t live to see over a million people march through the centre of London against the Iraq War, their voices ignored by the Prime Minister of the day.

From time to time the police infiltrated our group. A moustachioed Scottish man, Dave Robertson, aroused suspicion because he was always driving a different car. When challenged he claimed to be working for a car rental firm. On another occasion he’d told me he worked at a club called the Tatty Bogle. One of the comrades went down to check it out and found this to be untrue. At Manu’s suggestion, we didn’t confront Dave, but assigned him the most onerous tasks: collecting heavy banners and placards in his car and carrying them on marches. He was always called upon to buy everyone drinks and asked to memorise long passages from James Maxton, an obscure Scottish Marxist.

The funny thing was, I quite liked Dave. He was always good-natured and went along with the aggravation. Then all that changed. The sinister nature of his work revealed itself.

Through the Union, I’d got a job at the Daily Mirror and an Irish workmate, Ethel, came along with me to a meeting at the London School of Economics. John Gittings, a Guardian writer, Malcolm Caldwell of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Manu and Pat Jordan of the International Marxist Group were getting an Indo-China Solidarity Committee together to respond to Nixon's bombing of Cambodia. Ethel was interested in becoming involved. Dave was there. When Ethel saw him, she greeted him brightly. ‘Oh, I know Dave,’ she said. He grabbed her by the wrist and said, ‘I want to talk to you outside.’ They didn’t come back.

Next day at work, Ethel was cool and awkward with me. After a week of this she asked me to meet her for a drink.

‘Dave works for the special branch,’ she told me. ‘He’s threatened that if I tell you or Manchanda, he’ll cause something nasty to happen to my family in Ireland.’

Dave disappeared off the radar and was never seen again. For a few months I scrutinised the faces under policeman’s helmets, wondering whether Dave had been demoted back to pounding pavements as a beat bobby.

The comrades presented us with a red plastic carrycot. Manu found a broken pushchair on a skip and we used that for wheels. The back of the chair wouldn’t stay upright, so we kept it flat and placed the carrycot on top.

‘The best support we can give the Vietnamese people is to have a revolution here,’ Comrade Chris asserted.

‘Have a little humility, comrades,’ pleaded Manu, rocking the baby on his knee. ‘Do you think the British working class is going to make a revolution any time soon? Stop all this arrogant nonsense that the British working class is the most advanced in the world. They’re the most backward in the world, the most racist in the world. The British working class benefits from imperialism every day.’

Comrade Chris flounced out of the room and, as she attempted to slam the door, her handbag became entrammeled and she was forced to return, which I found very funny. Laughter soured my relationship with Comrade Chris.

The comrades were becoming impatient, tempers fraying. We were in a hurry to make the revolution happen, ever waiting for the proletariat to kick into action. Surely the revolution was just around the corner, like the next bus?

For the first six years of Chu Chu’s life, we lived in the ground floor flat at 58 Lisburne Road in Hampstead, the place where Claudia Jones died on Christmas Day, 1964. As I write, campaigners are still petitioning the London Borough of Camden to place a blue plaque on the house. Had Claudia spent her last hours reclining on the same battered chaise longue upon which Manu rested and worked as long as we lived there? Every day I’d carry the baby upstairs to be washed in the

bathroom we shared with the family living on the upper floors. There was no lock on the door and where the lock should have been was an eye-sized hole, which the kids liked to peek through while we were taking baths. Our lavatory was in the garden outside the back door.

We became used to the white van with cables and aerials protruding from its roof that was permanently parked in Lisburne Road.

‘Special branch,’ Manu said. Once, when we were on a bus on the way to a demonstration, Manu mischievously asked the

conductor to collect our fares from two men who’d been clumsily tailing us. They paid up. I found it difficult to comprehend why our puny efforts caused so much concern to the authorities when everything we did was within the law and totally transparent..

‘You can go down to Speakers’ Corner and let off as much steam as you like,’ Manu explained, ‘and the nice, docile policemen will stand by, smiling. But if you challenge the state directly and start to turn public opinion about the war, that has to be quashed.’

He didn’t live to see over a million people march through the centre of London against the Iraq War, their voices ignored by the Prime Minister of the day.

From time to time the police infiltrated our group. A moustachioed Scottish man, Dave Robertson, aroused suspicion because he was always driving a different car. When challenged he claimed to be working for a car rental firm. On another occasion he’d told me he worked at a club called the Tatty Bogle. One of the comrades went down to check it out and found this to be untrue. At Manu’s suggestion, we didn’t confront Dave, but assigned him the most onerous tasks: collecting heavy banners and placards in his car and carrying them on marches. He was always called upon to buy everyone drinks and asked to memorise long passages from James Maxton, an obscure Scottish Marxist.

The funny thing was, I quite liked Dave. He was always good-natured and went along with the aggravation. Then all that changed. The sinister nature of his work revealed itself.

Through the Union, I’d got a job at the Daily Mirror and an Irish workmate, Ethel, came along with me to a meeting at the London School of Economics. John Gittings, a Guardian writer, Malcolm Caldwell of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Manu and Pat Jordan of the International Marxist Group were getting an Indo-China Solidarity Committee together to respond to Nixon's bombing of Cambodia. Ethel was interested in becoming involved. Dave was there. When Ethel saw him, she greeted him brightly. ‘Oh, I know Dave,’ she said. He grabbed her by the wrist and said, ‘I want to talk to you outside.’ They didn’t come back.

Next day at work, Ethel was cool and awkward with me. After a week of this she asked me to meet her for a drink.

‘Dave works for the special branch,’ she told me. ‘He’s threatened that if I tell you or Manchanda, he’ll cause something nasty to happen to my family in Ireland.’

Dave disappeared off the radar and was never seen again. For a few months I scrutinised the faces under policeman’s helmets, wondering whether Dave had been demoted back to pounding pavements as a beat bobby.

The Maoist precept of criticism and self-criticism was being acted out in a manner that guaranteed conflict. The issue of sexism in the group was endemic. One man who was accused of sexually harassing a woman comrade ‘defended’ himself by saying, ‘She’s too ugly to rape.’ This was not an isolated incident, as soon it emerged that there was also at least one case of domestic violence within the group. ‘Patriarchy within the organising space’ was a horrible reality.