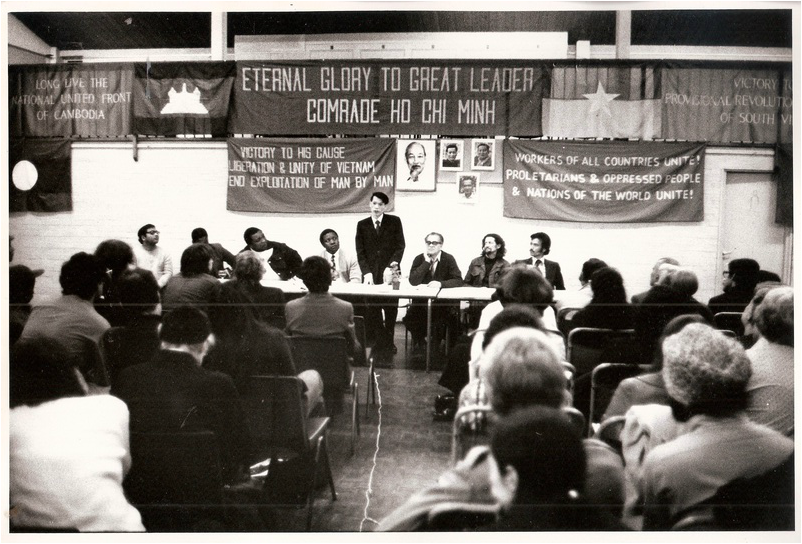

Manu at an outdoor meeting or performance, date unknown, place unknown. Copyright Manchanda Family Archives.

Manu at an outdoor meeting or performance, date unknown, place unknown. Copyright Manchanda Family Archives.

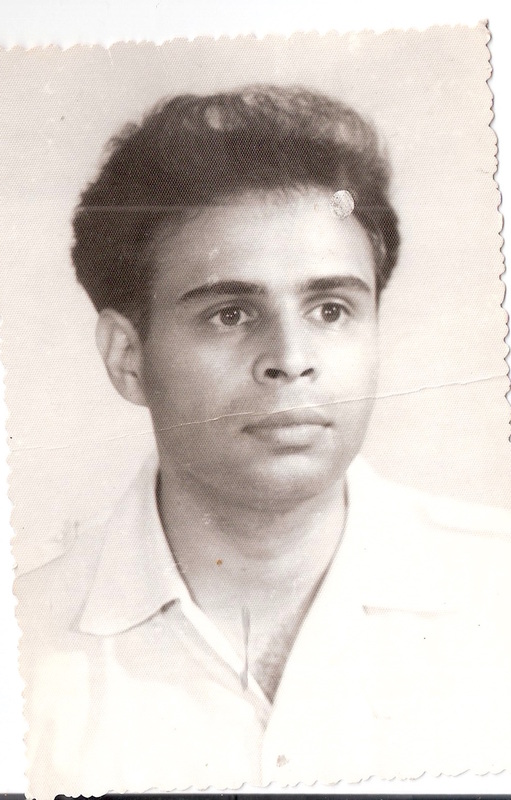

Manu was born in Gujranwala, India, on September 4th 1919.

His mother and father, Shrimati Janki Devi and Shri Chuni Lal Manchanda, were both active in the movement to end British colonial rule as members of the Indian National Congress [which bore no resemblance to the corrupt institution the Congress Party has become today]. Distant relatives with whom he was sent to live while his parents spent time in prison, mistreated him.

In the inter-communal bloodshed following the partition of the sub-continent the family were forced to flee to New Delhi after living for a while in Lahore. He was very proud of his mother, an early feminist, who refused to fast for her husband, according to tradition, unless he reciprocated. In recognition of her role in the anti-colonial movement, she received a freedom-fighter's pension until the end of her long life.

After joining the Communist Party of India, Manu worked night and day, helping refugees from every community, spurning false divisions such as religion and caste, which he saw as superstition. Disgusted by the lack of amenities provided for refugees by the new Indian Government, Manu took the initiative to set up tents on Nehru’s lawn to house thousands of people arriving from the other side of the artificial, hastily created border. It was a time when trains loaded with dead bodies were pulling into Indian railway stations.

He used to tell a story that demonstrated his philosophical approach. If you are hiding a refugee from potential killers, what do you say if you’re asked, ‘Have you seen a Muslim?’ He would answer an emphatic ‘No!' True or false?

Until he left the country, he worked underground for the party as a courier and was once arrested on a train, framed with plotting a bombing campaign, and jailed for a few weeks. While he was studying for a Bachelor of Science degree he also trained as a journalist. He was active in the people’s cultural movement, enjoyed singing and had a natural ability for playing musical instruments. He loved the music of The Mighty Saigal.

His friend, Inder Sen Gupta recalled that Manu left India to attend an International Youth Festival in Berlin. On 22nd July, 1952, he sailed tourist class from Bombay in the SS “Chitral” at a cost of £50 (667/13/- rupees). While there, he received a warning that he would be arrested if he returned to India. He decided to travel on to London.

As soon as he arrived in the capital he applied to The Observer for a post as a trainee journalist. His rejection letter was addressed to him at 82 Talbot Road, W.2.

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, Manu worked as a laboratory technician at Bedford College, as a labourer in the Walls ice cream factory, in a wine cellar, and he later taught in a south London school. He never kept a job for long because of his political commitments.

Bearing credentials from the Indian Party, he joined the Communist Party of Great Britain upon arrival in London, where he met Claudia Jones. They began a significant personal and political relationship, sharing the struggle against racism within the party after being told: ‘We don’t want colonial comrades to play a leading role.’

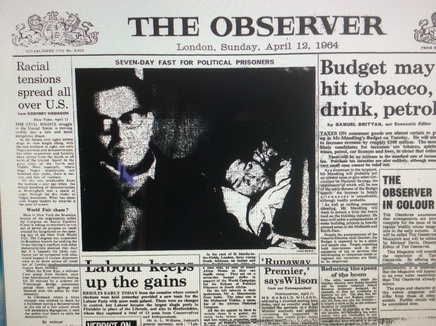

Experiencing the same cold-shoulder the Communist Party had shown Claudia, he joined her and others to form the Committee of Afro-Asian-Caribbean Organisations. Claudia appointed him managing editor of the West Indian Gazette. In April 1964, with three members of the African National Congress, he went on a seven-day hunger strike in the courtyard of St Martin-in-the-Fields in support of the worldwide campaign for the release of Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Rusty Bernstein.

PRESS RELEASE

AFRICA UNITY HOUSE

3 Collingham Gardens, SW5

April 8th, 1964.

After that his health began to fail. He was suffering from undiagnosed diabetes, a condition eventually detected by a young Vietnamese doctor when he visited Hanoi as a delegate of the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association.

In the sixties, Manu visited China twice and was inspired by what he saw.

It was while he was in Peking, in December 1964, that he received the news of the tragic death of Claudia Jones and he immediately returned to London, stricken by her death. While grieving he had to deal with an attempt by the Communist Party to take Claudia’s body and hold a party funeral. Mr Cumberbatch, a cousin of Claudia’s who had come from New York, took out an injunction to prevent a funeral being organised until Manu returned from China. On his return, Manu purchased a plot near Karl Marx' tomb in Highgate Cemetery and organised a funeral “fit for a head of State” (as Gertrude Elias described it)

He brought out two more issues of the West Indian Gazette, one of them from a hospital bed. It was in that final issue that he published an article, Partners in Aggression, criticising the Soviet Union for colluding with the United States in suppressing national liberation movements, particularly in the Congo. He was immediately suspended from membership of the party without being allowed to explain his stand to the Party Congress. He was subsequently expelled.

His statement to the party executive, hand delivered on October 29th 1965, speaks of ‘the hollowness, if not the hypocrisy, of the District Committee’s sympathy […] highlighted by the treatment that the party leadership accorded to the late Comrade Claudia Jones after her deportation from the USA which was a betrayal of the sacred trust of the American Party, the American people and especially the oppressed Negro people whose leader and representative she was.’ And, ‘[…] the most inhuman and vindictive behaviour of the Party leadership regarding her funeral.’

Almost immediately, the party rumour mill went into action, circulating a story that Manu had ‘sold Claudia Jones’ ashes to “the Chinese”.’ The party were intent on character assassination and kept up their efforts for decades.

Manu’s political work continued unabated with the Indian Workers Association, Friends of China, the Britain-Vietnam Solidarity Front and involvement in an attempt to form an ‘anti-revisionist’ political party composed of like-minded comrades, many of whom had left or been expelled from the CPGB.

In December 1965, the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation called for a mass campaign to end United States aggression against the small, far-off country of Vietnam. While the West Indian Gazette and Afro-Asian Caribbean News (as the paper came to be called) had carried news about U.S. imperialism’s machinations in South East Asia, it was not until the Russell Foundation gave their call that the campaign against the war took off.

On June 4th and 5th 1966, a conference was held in London to inaugurate the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign.

A group of Trotskyites who had taken control of the Russell Foundation refused to accept the National Liberation Front as the sole representatives of the South Vietnamese people. The Vietnamese delegation at the conference joined a walk-out. Manu had anticipated this and had booked another hall in readiness. The majority of delegates left the conference and went to the other venue where they set up the Britain Vietnam Solidarity Front.

The high point of the BVSF’s activities came on October 27th 1968 with a mass demonstration, when leaders of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, including Tariq Ali and Robin Blackburn, planned to end the rally in Hyde Park, calling Grosvenor Square ‘a death trap.’ They also argued that there had been previous demonstrations at the U.S. Embassy and they didn’t want to repeat themselves. On BBC Radio, Manu characterised Tariq as a ‘playboy who was going to take his supporters on a guided tour of London.’ Manu urged demonstrators to follow a route to the lair of American imperialism, the U.S. Embassy in Grosvenor Square.

The media were agog with excitement. There were horror stories of bomb plots and bloody revolution. American novelist, Mary McCarthy, wrote a lengthy feature in the Sunday Times colour supplement in which she agreed that the embassy was the place to go.

The demonstration attracted tens of thousands. Many would never have heard about it if they’d had to rely on the tiny resources of the organisers. The media had mobilised them. Lessons were learned from this and shortly afterwards the D-notice system was introduced for the vetting of news, particularly demonstrations and Northern Ireland coverage.

As a result of Manu’s political organising and teaching, scores of revolutionaries became educated in the role of the State, national liberation movements, British and American imperialism, the women’s movement, the Cultural Revolution in China, the basics of the capitalist system, the philosophy of Marxism and the tactics and strategies involved in organising, working with other groups to build alliances and the value of learning from the history of the struggles of working class and oppressed peoples.

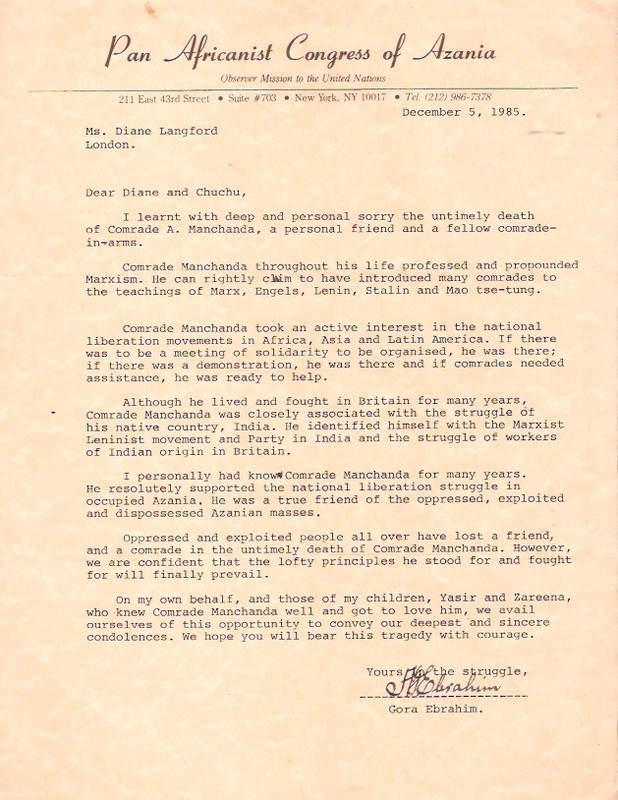

He encouraged people to think for themselves, question everything and overcome superstition and fear. During his political life he was constantly in the position of being in opposition and he argued with conviction and at times with crushing witticisms or sarcasm. Examples of political differences include the challenge he and Claudia presented to the Communist Party regarding the party’s failure to acknowledge, let alone oppose, the racism endemic in British society as a result of colonialism, their failure to address the super-exploitation of Black people, women in particular; the division within the Vietnam solidarity movement between those who sought to give solidarity rather than tell the Vietnamese people how to conduct their struggle; his opposition to the break away from Pakistan of East Pakistan which became Bangladesh (he saw this as another partition and pointed out the exploitation of the situation by the Soviet Union and India); the refusal of the anti-apartheid movement to recognise organisations other than the African National Congress; his alliance with the Pan-Africanist Congress of Azania and other national liberation movements that were opposed to Soviet domination; his support of the Naxalite movement in India; his support for China over India in the Sino-India War (1962) which led to him being declared persona non grata in the Indian Parliament; and his strong support for women’s liberation which led to estrangement from misogynist ‘comrades.’

Despite many bitter setbacks and twists and turns in the movement, Manu always remained optimistic. He used to say, “All roads lead to revolution, no matter how many twists and turns there are.”

Over the last four years of his life, he focused on his lifelong interest in alternative medicine, particularly homeopathy and succeeded in gaining a science-based degree in the subject. Homeopathy is ‘dialectical’ in its theory of ‘like cures like’, he believed. He had been looking forward to attending a seminar the weekend he died, on 27th October, 1985.

His mother and father, Shrimati Janki Devi and Shri Chuni Lal Manchanda, were both active in the movement to end British colonial rule as members of the Indian National Congress [which bore no resemblance to the corrupt institution the Congress Party has become today]. Distant relatives with whom he was sent to live while his parents spent time in prison, mistreated him.

In the inter-communal bloodshed following the partition of the sub-continent the family were forced to flee to New Delhi after living for a while in Lahore. He was very proud of his mother, an early feminist, who refused to fast for her husband, according to tradition, unless he reciprocated. In recognition of her role in the anti-colonial movement, she received a freedom-fighter's pension until the end of her long life.

After joining the Communist Party of India, Manu worked night and day, helping refugees from every community, spurning false divisions such as religion and caste, which he saw as superstition. Disgusted by the lack of amenities provided for refugees by the new Indian Government, Manu took the initiative to set up tents on Nehru’s lawn to house thousands of people arriving from the other side of the artificial, hastily created border. It was a time when trains loaded with dead bodies were pulling into Indian railway stations.

He used to tell a story that demonstrated his philosophical approach. If you are hiding a refugee from potential killers, what do you say if you’re asked, ‘Have you seen a Muslim?’ He would answer an emphatic ‘No!' True or false?

Until he left the country, he worked underground for the party as a courier and was once arrested on a train, framed with plotting a bombing campaign, and jailed for a few weeks. While he was studying for a Bachelor of Science degree he also trained as a journalist. He was active in the people’s cultural movement, enjoyed singing and had a natural ability for playing musical instruments. He loved the music of The Mighty Saigal.

His friend, Inder Sen Gupta recalled that Manu left India to attend an International Youth Festival in Berlin. On 22nd July, 1952, he sailed tourist class from Bombay in the SS “Chitral” at a cost of £50 (667/13/- rupees). While there, he received a warning that he would be arrested if he returned to India. He decided to travel on to London.

As soon as he arrived in the capital he applied to The Observer for a post as a trainee journalist. His rejection letter was addressed to him at 82 Talbot Road, W.2.

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, Manu worked as a laboratory technician at Bedford College, as a labourer in the Walls ice cream factory, in a wine cellar, and he later taught in a south London school. He never kept a job for long because of his political commitments.

Bearing credentials from the Indian Party, he joined the Communist Party of Great Britain upon arrival in London, where he met Claudia Jones. They began a significant personal and political relationship, sharing the struggle against racism within the party after being told: ‘We don’t want colonial comrades to play a leading role.’

Experiencing the same cold-shoulder the Communist Party had shown Claudia, he joined her and others to form the Committee of Afro-Asian-Caribbean Organisations. Claudia appointed him managing editor of the West Indian Gazette. In April 1964, with three members of the African National Congress, he went on a seven-day hunger strike in the courtyard of St Martin-in-the-Fields in support of the worldwide campaign for the release of Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Rusty Bernstein.

PRESS RELEASE

AFRICA UNITY HOUSE

3 Collingham Gardens, SW5

April 8th, 1964.

After that his health began to fail. He was suffering from undiagnosed diabetes, a condition eventually detected by a young Vietnamese doctor when he visited Hanoi as a delegate of the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association.

In the sixties, Manu visited China twice and was inspired by what he saw.

It was while he was in Peking, in December 1964, that he received the news of the tragic death of Claudia Jones and he immediately returned to London, stricken by her death. While grieving he had to deal with an attempt by the Communist Party to take Claudia’s body and hold a party funeral. Mr Cumberbatch, a cousin of Claudia’s who had come from New York, took out an injunction to prevent a funeral being organised until Manu returned from China. On his return, Manu purchased a plot near Karl Marx' tomb in Highgate Cemetery and organised a funeral “fit for a head of State” (as Gertrude Elias described it)

He brought out two more issues of the West Indian Gazette, one of them from a hospital bed. It was in that final issue that he published an article, Partners in Aggression, criticising the Soviet Union for colluding with the United States in suppressing national liberation movements, particularly in the Congo. He was immediately suspended from membership of the party without being allowed to explain his stand to the Party Congress. He was subsequently expelled.

His statement to the party executive, hand delivered on October 29th 1965, speaks of ‘the hollowness, if not the hypocrisy, of the District Committee’s sympathy […] highlighted by the treatment that the party leadership accorded to the late Comrade Claudia Jones after her deportation from the USA which was a betrayal of the sacred trust of the American Party, the American people and especially the oppressed Negro people whose leader and representative she was.’ And, ‘[…] the most inhuman and vindictive behaviour of the Party leadership regarding her funeral.’

Almost immediately, the party rumour mill went into action, circulating a story that Manu had ‘sold Claudia Jones’ ashes to “the Chinese”.’ The party were intent on character assassination and kept up their efforts for decades.

Manu’s political work continued unabated with the Indian Workers Association, Friends of China, the Britain-Vietnam Solidarity Front and involvement in an attempt to form an ‘anti-revisionist’ political party composed of like-minded comrades, many of whom had left or been expelled from the CPGB.

In December 1965, the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation called for a mass campaign to end United States aggression against the small, far-off country of Vietnam. While the West Indian Gazette and Afro-Asian Caribbean News (as the paper came to be called) had carried news about U.S. imperialism’s machinations in South East Asia, it was not until the Russell Foundation gave their call that the campaign against the war took off.

On June 4th and 5th 1966, a conference was held in London to inaugurate the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign.

A group of Trotskyites who had taken control of the Russell Foundation refused to accept the National Liberation Front as the sole representatives of the South Vietnamese people. The Vietnamese delegation at the conference joined a walk-out. Manu had anticipated this and had booked another hall in readiness. The majority of delegates left the conference and went to the other venue where they set up the Britain Vietnam Solidarity Front.

The high point of the BVSF’s activities came on October 27th 1968 with a mass demonstration, when leaders of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, including Tariq Ali and Robin Blackburn, planned to end the rally in Hyde Park, calling Grosvenor Square ‘a death trap.’ They also argued that there had been previous demonstrations at the U.S. Embassy and they didn’t want to repeat themselves. On BBC Radio, Manu characterised Tariq as a ‘playboy who was going to take his supporters on a guided tour of London.’ Manu urged demonstrators to follow a route to the lair of American imperialism, the U.S. Embassy in Grosvenor Square.

The media were agog with excitement. There were horror stories of bomb plots and bloody revolution. American novelist, Mary McCarthy, wrote a lengthy feature in the Sunday Times colour supplement in which she agreed that the embassy was the place to go.

The demonstration attracted tens of thousands. Many would never have heard about it if they’d had to rely on the tiny resources of the organisers. The media had mobilised them. Lessons were learned from this and shortly afterwards the D-notice system was introduced for the vetting of news, particularly demonstrations and Northern Ireland coverage.

As a result of Manu’s political organising and teaching, scores of revolutionaries became educated in the role of the State, national liberation movements, British and American imperialism, the women’s movement, the Cultural Revolution in China, the basics of the capitalist system, the philosophy of Marxism and the tactics and strategies involved in organising, working with other groups to build alliances and the value of learning from the history of the struggles of working class and oppressed peoples.

He encouraged people to think for themselves, question everything and overcome superstition and fear. During his political life he was constantly in the position of being in opposition and he argued with conviction and at times with crushing witticisms or sarcasm. Examples of political differences include the challenge he and Claudia presented to the Communist Party regarding the party’s failure to acknowledge, let alone oppose, the racism endemic in British society as a result of colonialism, their failure to address the super-exploitation of Black people, women in particular; the division within the Vietnam solidarity movement between those who sought to give solidarity rather than tell the Vietnamese people how to conduct their struggle; his opposition to the break away from Pakistan of East Pakistan which became Bangladesh (he saw this as another partition and pointed out the exploitation of the situation by the Soviet Union and India); the refusal of the anti-apartheid movement to recognise organisations other than the African National Congress; his alliance with the Pan-Africanist Congress of Azania and other national liberation movements that were opposed to Soviet domination; his support of the Naxalite movement in India; his support for China over India in the Sino-India War (1962) which led to him being declared persona non grata in the Indian Parliament; and his strong support for women’s liberation which led to estrangement from misogynist ‘comrades.’

Despite many bitter setbacks and twists and turns in the movement, Manu always remained optimistic. He used to say, “All roads lead to revolution, no matter how many twists and turns there are.”

Over the last four years of his life, he focused on his lifelong interest in alternative medicine, particularly homeopathy and succeeded in gaining a science-based degree in the subject. Homeopathy is ‘dialectical’ in its theory of ‘like cures like’, he believed. He had been looking forward to attending a seminar the weekend he died, on 27th October, 1985.